Episode 045: Alison Halsall

How do pictures and words help children imagine the world anew?

In this episode of Podcast or Perish, I talk with Dr. Alison Halsall, Associate Professor of Humanities at York University. She researches children’s literature, comics, and graphic novels, tracing how visual storytelling shapes childhood imagination and social awareness. We explore the artistry of the illustrated page and its power to teach empathy and wonder.

Transcript

Cameron: Alison, welcome to the podcast.

Alison: Hi, thanks so much for inviting me.

Cameron: It's been so interesting to look through the book that we're going to talk about.

You are a researcher of graphic texts, among other things, so I want to start with some definitions to help me kind of understand the boundaries of your work. How do graphic texts differ from the idea of an illustrated book? Like, say, Alice in Wonderland, that's got illustrations sprinkled amongst the pages, but I think of it primarily as a text book with pictures. You're talking about graphic texts. Can you describe or define what you mean by graphic texts?

Alison: Sure, yeah. Graphic texts, and by that I'm referring to comics and graphic narratives, are texts that tell a story in word and image. And what they require a reader do is to be able to do is to look at images and words together and separately.

So reading graphic narratives is somewhat different than reading picture books in that it requires a level of interpretation on the part of the reader that's not necessarily involved in reading picture books, for example.

Some critics assume that, there's a kind of simplicity in how words and images make meaning, right, that images are somehow transparent or easy to decode or understand.

And I push back on that. I don't think that's true at all.

Cameron: It sounds like there's a... kind of an expectation that that picture books are for kids.

Alison: Yeah, definitely. Yeah, that's exactly it. And that somehow they're transparent and easy to understand. And certainly there's a much more one on one connection between word and image in picture books for children, for sure. But in the texts that I look at, which are targeting an older demographic, these images, depend as much on rhetoric and argumentation as words do. And so, it's really important for readers to not take images as givens, right, but recognize that they're making an argument in terms of what they show. and sometimes it's more interesting to think about what they don't show. frequently these books that, these graphic texts that I've analyzed, use innovative methods that require a reader, a younger reader, a reader between the ages of roughly 8 and 18, to interpret how to read these images and sequence of images in relation to the text of the books themselves.

And what I find interesting in a lot of these texts is that sometimes words and images don't work together to make meaning.

The reader is really called upon to make meaning themselves. Right? Figuring out...

Cameron: Hmm, so there's a tension between the words and the pictures that they have to resolve somehow.

Alison: Yeah, they have to resolve it or figure out, like, wait a second, at, in, in one instance that I can think of, the narrative, per se, the literary narrative is not even addressing what's happening in the picture. So, readers are really forced to, or called upon to read the images on the page to figure out whether you read them traditionally, like, left to right, or, up to down, and think about how these images either visualize or don't visualize what the words are saying at the same time.

Cameron: It reminds me of some of the techniques that you get in novels from, I'm thinking of Dostoevsky onwards, where you've got things like an unreliable narrator, or you've got two chapters that cover the same events, one told from the perspective of, say, one brother and one told from the perspective of another brother, and they don't match up, right. So you get that tension in the narrative, in, in a novel. And so the graphic text that you're talking about, they've got this other layer they can play with as well.

Alison: Yeah. I'm thinking of one text in particular that I look at in my chapter on child soldiers. This text, written for older readers, Deogratias, about the Rwandan genocide,

a reader has to be very perceptive in terms of looking at the individual frames of the comics themselves because if a frame is black and sort of distinctive around the image, then that signals a particular temporal time or a time that they're discussing, likely in the past, versus another frame that lacks that panel margin. And, a reader has to distinguish that, and it might not necessarily be obvious to a reader on a first read. So frequently, some of these more challenging texts really require one or two reads to really distinguish some of the visual subtleties and narrative subtleties that the books make use of.

Cameron: So let's turn our attention to this book, since you've alluded to it. The book is called, Growing Up Graphic: the Comics of Children in Crisis. And I'm interested in a couple of things. One is how you identify the need to addess this theme, and then secondly, once you've got the theme, how did you go about picking which texts to include?

Alison: Sure. Well, Growing Up Graphic is my monograph that I've been working on for a few years now. I got into comics and graphic narratives specifically when I was a PhD student, TAing for a class on comics, and continued reading them, and I discovered as I was in my, reading paths that I gravitated to what I was starting to identify as a trend in comics and graphic narratives that feature memoirs or lived experiences of young people, specifically. And, that really pushed back on a number of assumptions that I had initially about comics and subject matter for comics.

I became very interested in this kind of documentary aspect of some of these texts for young readers that feature the lived experiences of children, young people, these young people who are living through crises of sorts or challenges or predicaments that they find themselves in and the point of the narrative is to show how they address those predicaments and in fact, with almost no exception in the texts that I used for the book, they feature the young people as agentic and in taking, yeah, a particularly agentic role in relation to their lives and their choices and the experiences that they're living through.

Cameron: That is so different from the media coverage of crisis situations where children are... passive victims, almost exclusively passive victims.

Alison: I know, well, it reminded me of that, of those terrible images, and I mentioned them in my book, of Alan Kurdi, who was a migrant with his family, who wasn't successful,

in escaping with their lives. And, those images of Alan Kurdi on the beach, and then picked up by the UN Peacekeeper, traveled around the world almost instantly, and really, sensationalized a terrible crisis, I feel, by means of those images and situating children specifically as, victims of abuse, victims of loss.

Cameron: By centering the children, these texts are producing an alternative perspective on these crisis events. So what is it about the fact that they're graphic that particularly enables them to do that?

Alison: Yeah, I think, first of all, I want to point out the, the use of the term "graphic" because, spoiler alert, a lot of these texts are quite graphic, in the sense that they feature violence and abusive behavior.

Cameron: Well, that's often the case for graphic texts. You know, if you think of, I'm not a big consumer of graphic texts, but when you flip through them at the bookstore, you'll notice that a lot of them have a lot of, a lot of blood splattering everywhere from the, from the events, for starters, right? And it's, it's like the artists feel they have permission to just go places that, I'd say, a different approach might not. You know, if you're writing about these events, then you're relying upon the reader to form the image in their mind, and you can allude to the violence in ways that the reader fills in the blanks. Graphic texts often fill in the blanks for you, and then you have to deal with that. So is that the kind of thing that you're seeing in some of these texts?

Alison: Well, and it's very unusual. I mean, for sure, the level of graphic violence in, let's say, like a Batman: Dark Night comic, Marvel comics, that is omnipresent in the genre. Those texts aren't consumed by the types of readers that I'm talking about in these texts.

Some of them are, marketed towards older readers, um, readers that sort of cross over into more adult readership.

So when I started seeing and reading these texts for specifically young readers that were much more graphic, in terms of, uh, blood and abuse and violence, I was, um, I was like, "How fascinating!" because what I feel that these texts really do is take away from that assumption that, that, "Oh, comics are just for kids. They're not interesting. They're not complex." All of these texts prove that assumption wrong,

and,

Cameron: Yeah, but they're also dealing with a different understanding of the childhood of the people, the characters in the books, right? These are kids who have experienced the stuff that's being drawn there. And we have, I think at one point, I'm trying to find where that... quote was, that in one of the books, there's this discussion between Maurice Sendak, uh, artist of sometimes of children's books, and, the author, Art Spiegelman, who drew the Maus comic, which dealt with all kinds of violent images and the Holocaust and so forth.

And the Sendak character in this comic talks about this "quaint and succulent" notion of childhood. Quaint and succulent. And it's this romantic notion of what childhood is that we would get from a Peter Pan novel or something like that.

And the children, the childhoods that are expressed in these graphic texts are so different from that.

Alison: Mm hmm.

Cameron: And is it something about the graphic text that allows... the author to push into that in a particular way, you know, the way that someone just writing with words wouldn't be able to?

Alison: Mm-hmm. I think they do. And I love that, comics dialogue between Sendak and Spiegelman because, of course, those two characters are such... visual greats, not only in the picture book tradition, but in the comic book tradition, as you indicated, with, Spiegelman's important work on the Holocaust and 9/11. And what was so fascinating to me when I read that New York Times [correction: The New Yorker, September 27, 1993] comic, and it was back in 1993, is Sendak's claim that you can't protect kids. They know everything.

And what was so captivating for me about that claim was that, Sendak's really arguing against that idealized vision of childhood innocence that you can see as far back as William Wordsworth and William Blake.

And, what's so fascinating about this claim that Sendak makes is that it really points to this idea that there's a desire of an adult for this vision of sheltered and pure and innocent childhood that doesn't say anything about the child, but it says more about the adult themselves, right? And...

Cameron: We need that image of childhood somehow.

Alison: We do, yeah.

So, what's so fascinating, I mean, I talked earlier about the rhetorical thrust of comics. What's so fascinating about this comics dialogue is that Sendak is making quite a radical revisioning of this view of innocent childhood that he argues speaks more about adults for what children and childhood stand for. What I like about that is that it really captures this need that I'm now seeing followed through in this new trend in, in graphic narratives about children in crisis, where children aren't innocent. The lived experiences that they're going through speak to a level of knowledge and even political activism that is so refreshing, so different from that vision of sort of like cupids flying through the air and sort of chubby and rotund, and innocent and perfect.

Cameron: I'm just wondering how these texts appear to readers in countries where that romantic notion of childhood isn't the norm.

Alison: Yeah, well, that's when I was determining, you know, you asked me about the scope of the project. When I was determining the types of texts I would use, I am still finding that text based comics are more created in the Global North by Global Northern writers. And so... what's fascinating to me is that they are specifically engaging and pushing back against that assumption of innocence. And I feel not doing it in an exploitive way at all. But rather, a number of these texts are published by publishers who are specifically, whose mandate is to share ideas about the world with readers, young readers, to expand their knowledge about world issues the world over.

Cameron: So do you think that graphic texts have a different ability to cross cultural boundaries somehow than the written word?

Alison: I think so. I mean, practically speaking, a lot of these publishers, comics publishers can and do interact with markets and, uh, they have distributors that can circulate these narratives a little bit more easily than, a text based narrative, and of course what I'm seeing as well is the use - and this isn't a focus of my book per se, but it's definitely something I'm interested in - many newer texts about migrants, for instance, are making use of the web format, so that they can capture and, capture the story and release the story faster, and potentially to a wider audience. And of course, the digital platform is very useful for that.

Cameron: Do you see the effect of access to the web having a difference for people who... wouldn't be able to have contact with, say, a North American publisher of a book.

Alison: Definitely, yeah, I mean, I follow one, I follow a number of comics creators on Instagram, right? They only publish on Instagram. And you can buy some of their work. The bio links you to their website, which allows you to buy their prints or what have you.

So absolutely, web-based comics have an ability to transcend boundaries and transcend regions of the world and as I said, have a much wider audience potentially than a text that is published by like, say, a small press that has limited distribution rights.

Cameron: So, I'm not familiar with the distribution of these different texts that you've selected. were they web first and paper later, or most of them paper?

Alison: Yeah, it's a great question. Some of them were web-based first, and then the creator was invited to transform them into a more lengthy text that was then circulated in book format. Generally speaking, though, all of these texts are published by European or North American publishers.

Cameron: Let's talk about the way that the book is organized for a second. You've got this vast sample of potential graphic texts that are related in some way to this theme that you've identified about children in crisis. How do you go about making sense of that and coming up with the categories that you end up putting in the book?

And I'll just list the categories for the listener. you have a chapter about child soldiers, you have a chapter about migration, immigration, so forth. You have a chapter about indigeneity in various forms. You have a chapter about, LGBTQ+ topics. And you have a chapter about disability and illness.

And all of these are done in relation to the experience of children being expressed in graphic texts on these topics. So how did you come up with those five categories?

Alison: Well, I started doing a really deep dive into graphic texts for younger readers, and I cut off the readership at 18, because I had this sort of general idea that I wanted to look at and find text.

Cameron: Could you define, how do you know who the readers are? How do you define readership?

Alison: Generally, the books are tagged by, by the publishers as being directed towards a particular demographic.

Cameron: So it's not necessarily capturing everybody who looks at those graphic texts, but it's the target audience from the publisher's point of view.

Alison: That's right. Yeah, that's right.

And in a few instances, there was a little bit of leeway that I was willing to experience, or to assume, simply because I wanted to look at it in relation to a number of other texts. Like in the child soldier chapter, Deogratias, as I mentioned, targets audiences according to the book details from 16 upwards.

So, obviously, in its graphic nature, it's looking at older readers, whether those are more mature readers who still fall under the 18-and-under, but who could also be adults. But generally, the books that I started to read widely in, were books that were looking at younger readers. And so, I read widely and I actually began with what was then, five years ago, a really interesting trend here in Canada, which is comics and graphic narratives about the Indigenous experiences. And I sort of devoured those, and then started expanding from there, and I started to see some really interesting trends. I noticed that there were some, as you said, texts about child soldiers, which is fascinating to me. And then, a new and very important continuing trend is comics about migration and the diasporic experience. And then, of course, what continues in, certainly since 2010, is a new preoccupation among graphic texts of queer experiences. And, one of the most, uh, sort of current trends in comics criticism is this idea of graphic medicine. And funnily enough, that was cropping up in comics for young readers as well. And then it just, I fell into the COVID comics during COVID.

Cameron: Mm

Alison: Those are not book texts primarily because, of course, in order for me to have accessed them so quickly, they had to be primarily web-based and, but, with one or two exceptions. There are a couple of books of COVID comics, but, yeah, so,

Cameron: I still think of comics as kind of a lighthearted look at the world, and when you say COVID comics, I have experienced this dissonance.

Alison: I know, I know, I know, and, and what was fascinating to me was sort of the mixed use of comics in terms of strategies for dealing with COVID. There are a number of webcomics that I explored in Africa, actually, that made use of the comics form to disseminate important safety knowledge to a wider group of people, and they were using the comics form to do that.

And that was really exciting for me, and sort of on a slightly different note, there was an interesting set of comics, when I was writing about migrant comics that were German language comics. They didn't make use of word, it was purely visuals, but it was fascinating to see how they were making use of those comics to provide information to recent immigrants to Germany about how to fit into the culture.

So that was fascinating to me as well, just to push back against that idea of the transparency of visual, visuals, because clearly, both of these types of comics were being used to prove a point or to make a point, to communicate information and even offer direction.

Cameron: Yeah, very didactic.

Alison: Very didactic.

Cameron: Mm hmm. I'm always interested in the broader question of academic research in terms of, like, how does this differ from simply a descriptive work, you know, listing texts that fit into these categories. There's got to be some, to me, for it to be an academic work, there's got to be some aspect of trying to make sense of things in a way that you can then move on beyond these particular texts and apply what you've learned in other settings and, loosely speaking, that's theorizing what you're seeing. How would you describe the role of theory or sensemaking in your work on these texts?

Alison: Well, one of my... one of my purposes in my own research, I feel a sense of responsibility in terms of use value to the work that I do, and that certainly is something that translates into my work on LGBTQ+ comics, et cetera, but, what this book is doing is pushing back against this idea of children as apolitical, and insisting that we need to bring them into conversations and listen to their voices about the world around us, because many of the thoughts that they have to share are important.

Cameron: You move from these five chapters to a conclusion that points in the direction of comics and graphic texts and COVID. And there's such a profound relationship, I think, in our society between children, often objectified in some useful political way, and public policy around the pandemic. And I'm wondering what we can learn from these graphic texts where the children have such agency for reinterpreting our understanding of the pandemic and the role of government, the role of corporations, the role of individuals.

Alison: Yeah, well, I think these texts really find themselves at an interesting nexus in relation to what's happening in, um, our cultural and political climate with regards to censorship. And so what these books insist on is that children are complex and they can cope with knowledge. And, what this pushes back on are these adultist assumptions that, that really fuel the censorship debates that we're hearing so much about.

And so I think it's very important to affirm these voices of young people rather than to shut them down. Because, especially in this current, this digital age, where kids are having access to devices and internet exposure, they are becoming aware of issues at a much younger age. And so, this idea that they can't cope with these, with complex thought or complex ideas, it's just... futile, and, you know, I really think leads to this divide that we're seeing between how someone like, you know, we were talking earlier about Trump, how someone can, you know, pretend or present a vision of the world that is simply not reality, versus younger readers who we should be training to read and think about assertions that adults are making, in a critical way. and so these texts really affirm that vision of child readers as being able to push back on, on some of these disturbing trends in our own sociopolitical climate.

Cameron: So, when you talk about censorship, are you talking about what children are allowed to see or are you talking about it in a broader sense?

Alison: I'm talking about what children are allowed to read in books, and books as sources of censorship. A number of the books that I look at in Growing Up Graphic were banned or are on the list of banned books.

Cameron: Right. So, you're talking about this incredible trend starting in the U.S. of right-wing censorship of what children would be allowed to read. I see. Yeah. Yeah. Well, I can imagine, you know, if you find Catcher in the Rye disturbing, then you're gonna, you're gonna be very worried about some of these graphic, graphic novels.

Alison: I was talking about this list of banned books to some family over Thanksgiving and...

Cameron: Well, that's a great topic over Thanksgiving dinner.

Alison: I know, something light hearted. And they were, they were like, okay, well, what are some examples of banned books? And they're really so ridiculous now when you look at some of these texts that we had to read in high school that are now the subject of book bans.

And it's just so, um, disturbing, really, in terms of trying, it's thought control, it seems to me, that, you wouldn't allow a young person to read Catcher in the Rye, or 1984, or, you know, some of my queer texts, you'd think, "Oh, they couldn't possibly cope with that," and that's just farcical. I mean, oftentimes young readers use that experience and that practice of reading to muse in their own mind about, you know, developmental, physical changes to their bodies, to muse about topics that they've heard about in school but might want to learn more about, etc.

So, there's those moments, those personal moments of reading are so key in the lives many young readers.

I think in that personal act of reading these texts, young readers allow those lived experiences into their readerly world for the, time that it takes to read the text and think about it as well. So, yeah, it's, I think that is primarily one of the important takeaways of these texts that I'm seeing with more frequency, and that is a desire to bring perspectives that we might not necessarily have in our own privileged, Global Northern, middle class, white, et cetera, life, and sort of be invited into a story that asks us to reflect about the limits of our privilege.

Cameron: Your faculty profile lists your interests as, um, besides the graphic texts it says you study Victorian literature as well. Is that completely separate from the graphic text or do you see some sort of a connection between them?

Alison: Well, funnily, there is a connection. It might not necessarily be obvious, but, uh, in my PhD, I was qualified in Victorian and modernisms. And one of my main focuses in my project there was visual illustration. And so one of the groups that I worked on in detail was a group of 19th century artists called the Pre-Raphaelites. And, I found a manuscript at Yale that was written by one of my favorite modernist poets that retold the story of, the history, that is, of the Pre-Raphaelites. from the perspective of, one of their models and muses. So, the project was really exciting because all of a sudden I was looking, I, you know, engaged with art theory, and so the project is very interdisciplinary in that regard. It's not simply English literature, and it transcends into visual art. And then what was fascinating was the modernist component, as well, because here we have this woman, H. D., who is a modernist poet who writes a giant like triple-decker typical 19th century novel about the Pre-Raphaelites, and from the perspective of a woman. And sort of retells that story in a very feminist way. And then again, part of what I did for the dissertation was produce a critical edition of the manuscript, which was such a thrill as well, because I could go down and work at Yale with the manuscript and the versions. And I got that kind of materialist experience of working with manuscripts that is such a thrill.

Cameron: Yeah, I know what you mean by that. Tell me some art theory. What do you mean by art theory? There's no theory in art, just drawings.

Alison: Oh, beginning from like John Berger's Ways of Seeing and, you know, thinking through perspective and the perspective of female artists versus male artists. I kind of went down, in my fourth chapter, I remember looking at ghosts and spectrality in terms of Jacques Derrida and his work on painting. He's actually done some work on painting as well. And so that was, I went into some really unexpected places,

Cameron: Huh!

Alison: But really enjoyed it.

Cameron: Yeah, it sounds like a lot of fun. And I'm particularly intrigued by this, work that is telling the story of these Pre-Raphaelites from the perspective of their model. That's flipping things around.

Alison: It is, and of course, as you can imagine, it's not flattering to the men.

Cameron: Oh dear.

Alison: Not flattering! So, and that's sort of the unique perspective that a woman writing in close to mid-20th century could provide that a model at the time in 1880s could not. That was interesting to me to see the particularly modernist take on the Victorians and to think through also periodization. Sometimes in English, I know we're moving away from this, but we can think about individual periods, right, literary periods, but really, it's not as easy to draw those boundaries, when you're dealing with texts and real people writing, so for me it was like, it was exciting to look at text, visual text, literary text from the mid, sort of 1860 to 1890s, and then, see how those ideas followed through into the modernist period.

Cameron: Now, you as an academic, you're wanting to get your work out to a broader audience, not simply other academics, and so you decide to publish a book. There's another of your books just over your shoulder in the video that I'm looking at, the LGBTQ+ Comics Studies Reader. Do you want to tell me a little bit about that, briefly?

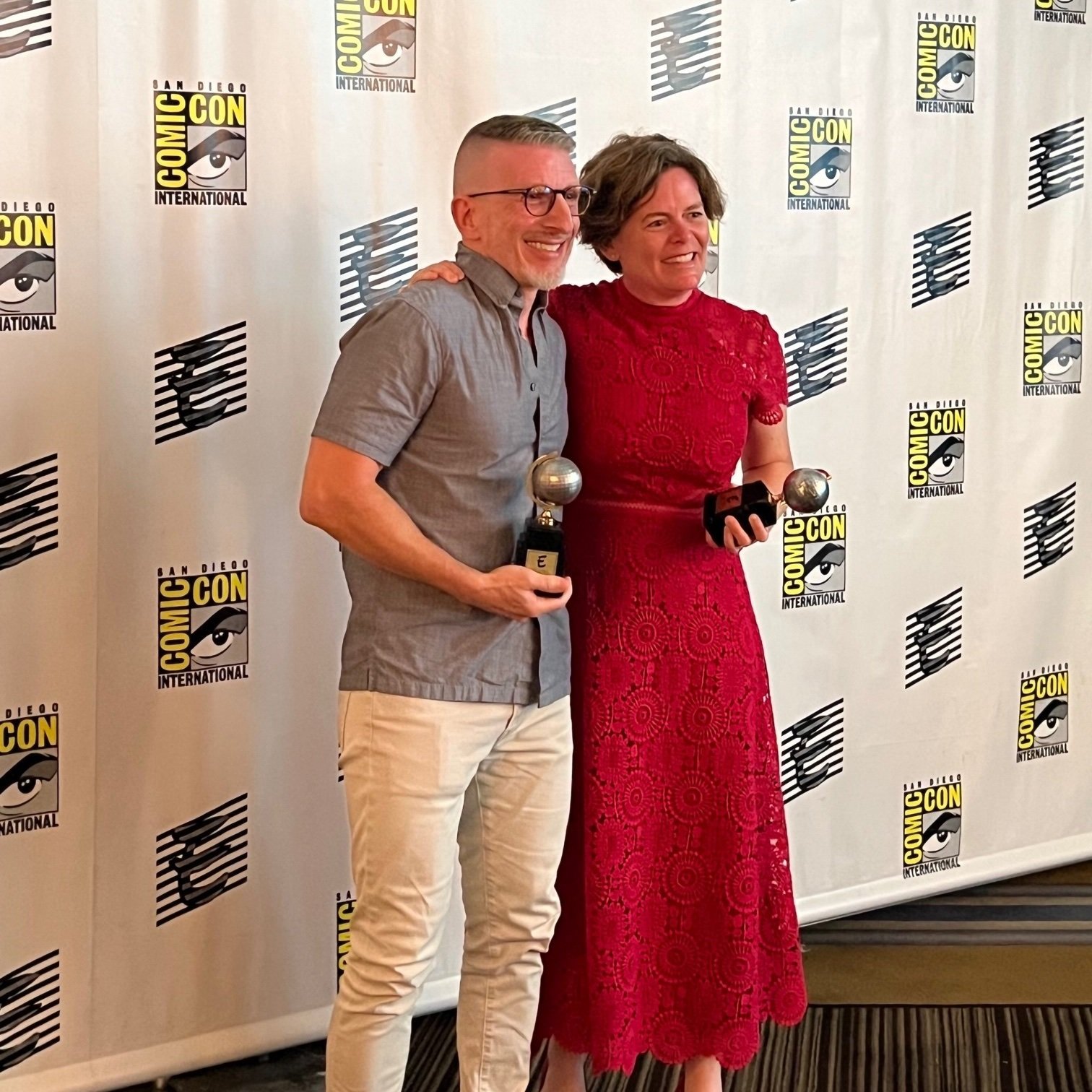

Alison: Sure. Yeah, that's another labor of love. My colleague, also at York, Jonathan Warren in the English department, he and I started working together on this collection of essays about LGBTQ comics criticism. It's the first of its kind. It had never been done before we did it. It took a while for it to come to fruition, but, wonderfully, in July, we were awarded the Eisner Award, which is, like, the highest award in comics criticism.

Cameron: Congratulations!

Alison: Thank you! For the best academic book about comics. So, we got to go to Comicon, which I had never gone to. That's where the Eisners are presented at this beautiful, like, Oscar-calibre, awards show, and we

Cameron: Who were you wearing?

Alison: I rented a dress, and I have to say, people enjoyed my dress.

Alison Halsall with co-author Jonathan Warren, at Comicon after accepting the Eisner Award.

Cameron: Lovely.

Alison: So it was a real thrill and such an honor, and you know, we had to make a speech to thank, and I used that opportunity,

Cameron: Did you get played off by the orchestra?

Alison: There was music, yes, I used our speech to thank our readers for taking a risk on us. That type of book is controversial in this day and age, sadly, especially in the States. And, especially published by Mississippi University Press. I was just really grateful that people saw the value of it and voted for it. Because, I mean, it was nominated, so it was one of five nominated, but then, readers have to vote, like, people in the comics industry have to vote on the winner. And so, it was such an honour for both of us that our book was selected.

Cameron: Wow, that's a wonderful story and I'm so glad to see you getting recognition. Alison, it's been just a delight to talk to you about your work. it's so lovely to talk to someone who is so emotionally engaged in their own work.

Alison: Oh, thank you so much, Cam. I've so enjoyed our conversation.

Cameron: All right, thanks very much.

Alison: Okay.

Alison Halsall

Links

Alison Halsall’s faculty profile page

Credits

Host and producer: Cameron Graham

Photos: Susan Dieleman

Music: Musicbed

Tools: Descript, Squadcast

Recorded: October 18, 2023

Location: Toronto